I was sitting in the back of a college class one day letting my mind wander over some music theory while the professor spoke about something that was probably important for the final. I had a bit of a realization that slapped me upside the head. I couldn’t believe I’d never thought of this before. I jotted a couple notes down and sat restlessly waiting for the class to be over. The moment I was I ran home to my basement apartment off campus and picked up my guitar. Sure enough, it worked! I found the method for determined all of the chords in a key.

What I aimlessly stumbled upon was the concept of diatonic chords in a key. This is not groundbreaking by any means, and a very early and basic concept in music theory that most pursuing that study run into long before I did. However, to me this was a dramatic shift in the way that I approached playing guitar, writing songs, and using my ear to suss out chord changes. So to cut to the chase, this is the concept of diatonic chords (or the thing I wish I’d known sooner).

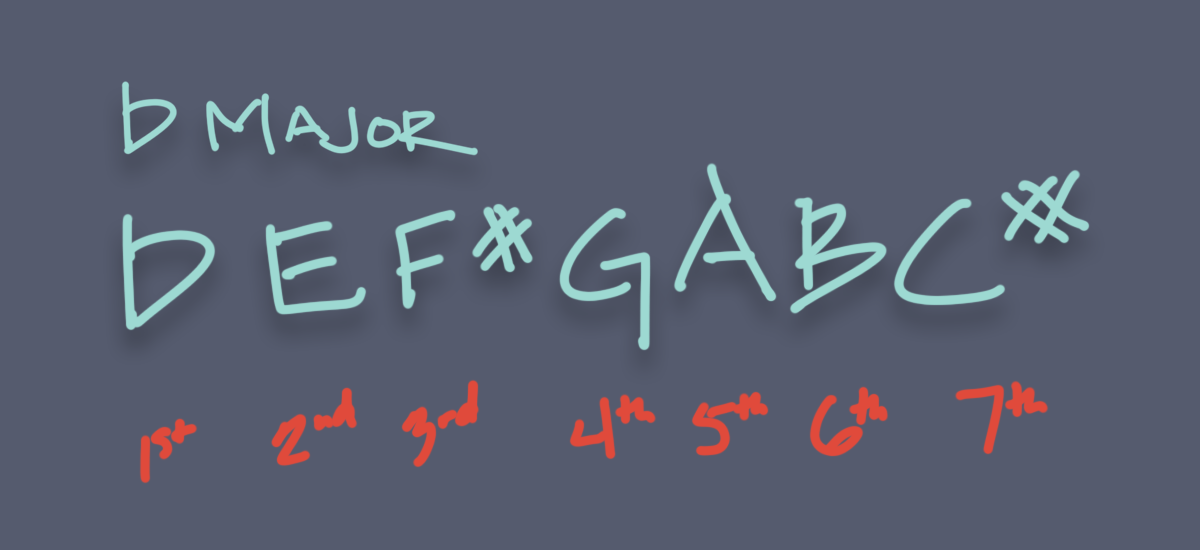

For this example we’re going to use a major key, however you can use whatever scale you want (major, minor, melodic minor, harmonic minor, etc.) And before we dive into the chords, let’s revisit how a major scale is constructed. In this case we’ll use the key of D. I’m not using music notation, just note names for this.

Now if we assign a number to each of these notes, they will be called ‘degrees.’ So the second degree of the D major scale is E.

Now that we have all of the notes that occur in the D major scale, we can use these available notes to build chords. A chord, is any harmonic set of pitches consisting of two or more (usually three or more) notes (also called “pitches”) that are heard as if sounding simultaneously. [wiki]. So basically, a chord is any two or more notes played together. Ok, that’s easy to do, but what’s not as easy to do is making those two notes actually sound good together. We’ll start constructing chords with a simple triad, which is as it sounds made up of 3 notes. These three notes are the 1st, 3rd, and 5th degrees of the scale.

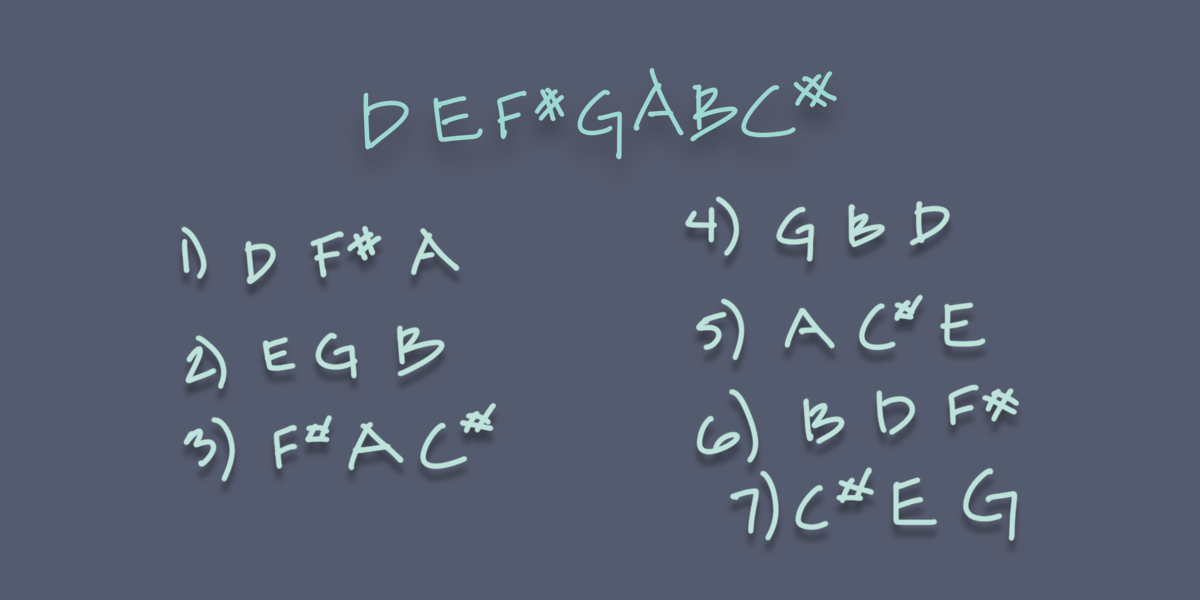

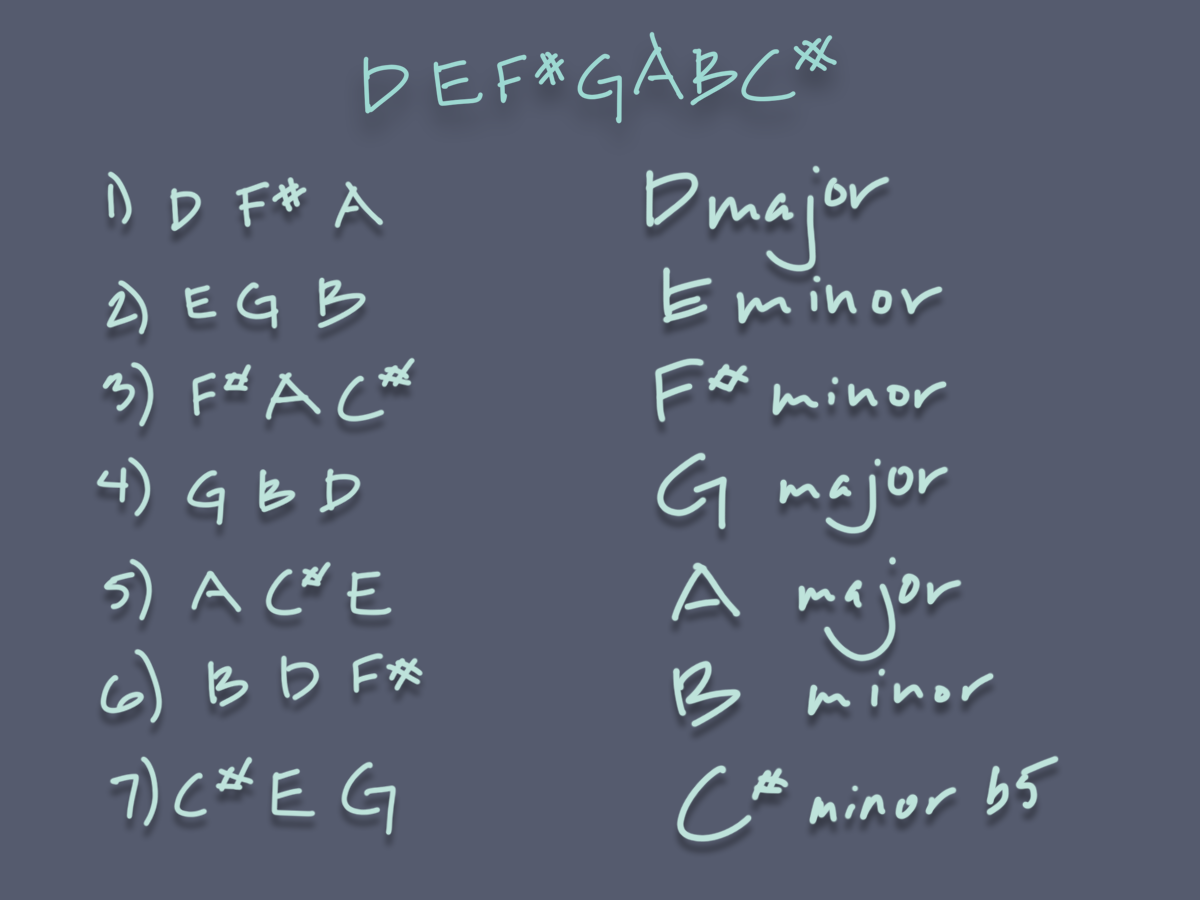

Now we can do this for the rest of the notes in the scale

To be very explicit, all I’m doing here is taking the note I want to start at and making that note #1, then re-assigning all the notes with numerical values 1-7 and pulling out notes 1, 3, and 5. This makes up our simplest triad. Now, we have one more step here. We have to take all these notes and figure out what type of chord they make. This will require just a bit more definition.

The distance between the root (your #1 degree in the scale), and any other note in the scale has a name based on how many semitones it is away. Read more about these intervals and their names under the ‘Quality’ section of this wikipedia article.

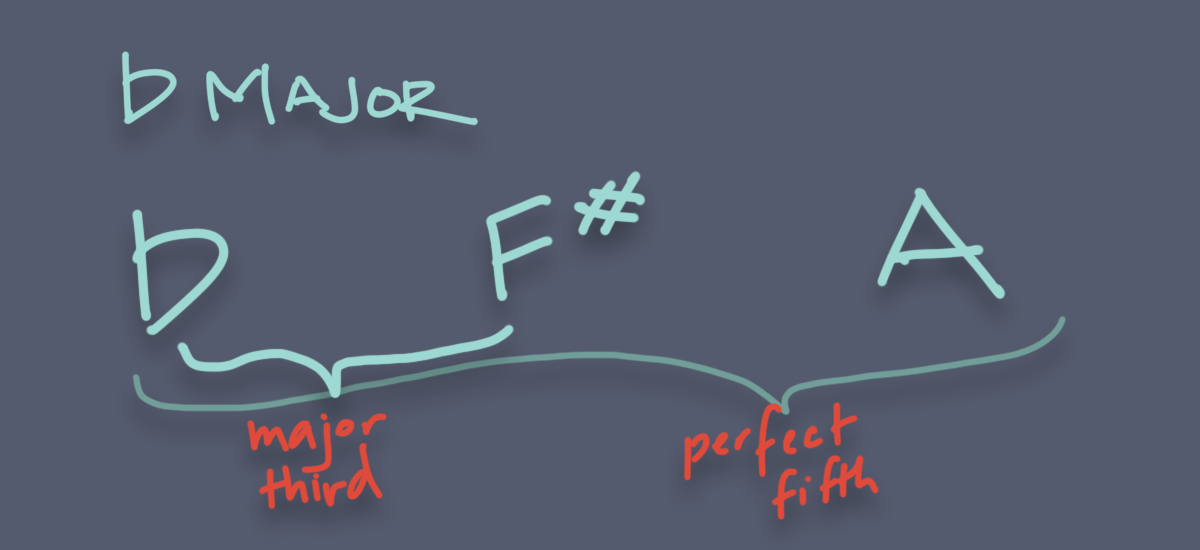

So now we can take the 1,3,5 groupings from all of the notes above and determine if they’re minor or major chords. Let’s start with the first one. We have D, F#, and A. F# is 4 semitones away from the D, which makes up a major 3rd interval as we can see from our reference above. And A is 8 semitones away from the D. Which is an interval of a perfect 5th. Together this makes a major triad.

One down! Now let’s take the second note E and do the same thing. So 1,3 and 5 starting on E is E, G, and B. G is now 3 semitones away (instead of 4 like in the D major chord) from the root E which makes a minor 3rd interval, and B is 8 semitones away from E which makes a perfect 5th interval. This gives us 1, b3, 5. Also known as a minor chord.

Doing this for the rest of the notes in the key of D, gives us these chords

And it’s really that simple. There are all of the chords that exist in the key of D major. Now if we take this one more level, let’s revisit that last image. If we take away the note names then we’re left with, in this order, major minor minor major major minor minor flat 5. Here’s the cool part. For any major key, this pattern remains the same. All you have to do is remember this pattern, and you’ll be able to know if that A chord in the key of G is a major or minor. (It’s a minor, as you now well know.)

If you’re feeling like pushing this even farther, add in the 7th note for all of these chords to get the more jazzy version of this exercise.

I hope that you found this useful, and easy to understand. If things don’t quite make sense, please leave a comment below and I’ll see what I can do to make this concept more manageable. This was a moment for me that allowed me to realize that music theory wasn’t as daunting as I originally thought. Until next time, make sure to pick up that guitar today!